On April 30th I joined a panel of business leaders at the GoGreen Seattle Conference to talk about what sustainability means to them. With businesses like Boeing and CenturyLink Field represented, trust me when I say Duna Fisheries, LLC with only two employees was the smallest in the pack! Crazy, huh? Anyway, here’s what I had to say:

My name is Amy Grondin. Part of the year I make my living as a commercial salmon fisherman. When not on the water, my work is in Commercial Fisheries Outreach with a focus on sustainable food systems. I rely on salmon to make a living and see them as a very important business partners.

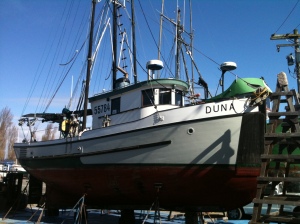

F/V Duna, our 40’ wooden fishing boat, was built in 1936 in Tacoma. My husband Greg and I fish together. Sometimes we’ll hire a deckhand for a few weeks if the fishing is predicted to be particularly good and a third set of hands would be helpful.

Greg and I fish in Washington and Alaska. Our salmon fishing season begins off the coast of Washington on May 1st. Towards the end of June we’ll stop fishing Washington waters and start the trip to Southeast Alaska where we’ll fish for the rest of the summer. Come September the fishing slows down and the crew of two is getting tired. This time of year each day starts and ends wondering if the autumn storms are coming and if it’s time to stack the fishing gear and head south with the geese that are flying overhead. It is a good life for us and we look forward to working on the water.

We catch salmon by trolling, which is often called hook and line fishing. Trolling is a very sustainable fishing technique as each fish is caught one at a time. If the fish caught on a hook is too small to keep or not of the right species it can be released alive to swim away. Often trolling is confused with trawling as the names of these two fishing techniques roll of your tongue in a similar way but the similarity stops there. Trawling involves catching fish with a net that is dragged behind a fishing boat in deep water very near the sea floor. Fish caught by trawling are not alive when they are landed on the boat so there is no chance to release fish that are not your target species. In the jargon of fisheries, trolling is a selective gear type while trawling is nonselective.

When we are fishing our boat is our world. We take care of our boat as if our live depended upon it, because they do. Each year before we go fishing Duna is hauled out in the boatyard where we clean and inspect the hull, make necessary repairs, apply fresh paint and back in the water she goes. The engine is tuned; the wiring and hoses all checked; and safety gear inspected.

We trust our boat is safe because we know that we have done all we can to make it that way. Once fishing begins we want our time to be spent fishing, not trying to make repairs at sea or worrying about breaking down. That is not to say that boat maintenance ceases once fishing begins. It just becomes part of our daily routine, which is something like this:

Morning comes. First thing turn on the computer, GPS and navigation program. If they don’t launch on the screen nothing else happens until the system is up and running. Next down to the engine room to start the engine but first check the oil level. All day long while fishing watch the engine gages for temperature and oil pressure. Look in the bilge many times a day to see if any seawater is gathering. Water should be outside of the hull, not in it. Also, look in the bilge for oil. An oil leak is bad for both the engine and the environment. Watch your fuel level to make sure there is enough to get you back to port after six days of fishing.

Engine started, up the ladder and out on deck. When the anchor is hauled check the chain for wear. Look up to see how the rigging above the boat is holding up. Any chaffing of lines or burrs on the stainless cable that tension the mast and poles to the deck? While at it check the sky, it will be obvious if it’s raining. Take note which of side of your face is the wind hitting. Scan the horizon for clouds or clearing, white caps or any other changes that might be coming your way. Sniff the air. All should be briny sweet since the deck was scrubbed after fishing yesterday. Smell fuel, other chemicals or a ‘hot’ smell? You shouldn’t and if you do drop everything until the source is found as it could signal a problem. Now make coffee and run out to the fishing grounds.

Maintaining the boat is only part of the equation. It is equally important to maintain the crew. Get sleep when possible, eat when hungry and drink if thirsty. Check the level of the fresh water tank, as drinking water is a precious commodity, maybe even more so than fuel. Keep dry if possible as it makes it easier to stay warm. Wear sunscreen, sunglasses or safety glasses when fishing. A hook in the eye is nothing you want and it happens to people every year.

Be safe on deck and don’t do stupid things. Think it through, look where you step, put things back where they belong, especially knives. Secure loose lines, tie down things on deck, wash slippery fish guts off the deck. Watch out for the other people on the boat and lend a hand if one is needed. Do everything you can to stay on the boat.

What does any of this have to do with sustainability or sustainable business practices? On the water Greg and I are very tuned into our fishing world. We monitor the boat, weather, sea conditions, fish and ourselves for changes. We conserve water, fuel, cook only what we will eat and in general try to keep all in balance because we only have what is on board the boat. The goal is to create as little waste as possible because there is nowhere for it to go but on the boat with you. This is the sea going equivalent of ‘pack it in, pack it out.’ We fish responsibly while trying to catch what fishing regulations allow us. If we take care of the fish the fish will take care of us by providing us with an income and food. When we do all these things the quality of life while fishing is very good. We make a living with a hard working crew while acting as stewards to salmon and the ocean. This is how our small floating business achieves triple bottom line results – a balance of people, profit and planet.

When fishing season is over and we are back on land, civilization at first overwhelming. Our home on land doesn’t roll around while we are sleeping. There is a seemingly endless supply of water from the tap. The garbage and recycling magically go away each week. The flick of a switch provides light and power that is not from a battery bank that is constantly in need of charging. Should the car run out of fuel you don’t need to worry about drifting onto the rocks like you do on the boat. Just call a friend, a tow truck or Triple A. No need to ration food, the grocery store is minutes away but why cook when you can go out to eat? Slowly, all the convenience dulls our survival instincts. It can be very easy to take for granted the resources that are just there for the taking. We become disconnected from the natural world and our role in it. How do we remember to live deliberately?

This is when lessons learned on a fishing boat about the stewardship of nature need to be recalled. Don’t get me wrong, civilization rocks! I love my warm, dry home; going out to dinner; the mixed blessing of constant connectivity through my smart phone; and knowing I can sleep through the night without getting up to check the weather.

The difference is that when Greg and I are on the boat, at sea and away from land we are very cognizant how our survival is directly tied to the quality and amount of resources we have access to, both natural and man-made. We don’t take any of it for granted or get casual about the value of fuel, shelter, water, or food. We are constantly aware of our connection to nature and the need to observe and respond to ever changing conditions.

At sea we share the ocean with the salmon we catch. We are part of the marine food web in the role of top predator. Back on land we are still connected to salmon but in ways not always tangible or as obvious as sea spray in your face. Fishermen return to land after fishing season closes. Likewise salmon leave the ocean to swim inland and up streams to spawn after their life at sea. Now the water connection to salmon is fresh, not salty. We need fresh water for drinking, washing, irrigating crops and creating hydropower while salmon need the water simply to spawn and complete their lifecycle.

No matter how you make a living – fisherman, computer programmer, construction worker, lawyer or [fill in the blank here with your own profession] – the fact that you live in the Pacific Northwest connects you to salmon. Streams and rivers thread from land to sea, stitching the two together inseparably. Choices and actions made daily have impacts beyond the four walls of our homes or four wheels of our cars. We may live in ‘rain city’ but water can’t be taken for granted. We need to protect it; keep it clean and remember that the less we use the more there will be for salmon. Living deliberately doesn’t have to mean a life of less. It means more for later.